SPRING 2017

We are pleased to present our spring 2017 issue of evolution, a seasonal journal. This issue offers our reflections on renewal, reuse, and reinvention of historic projects, followed by POSTINGS: a clipboard of recent engagements of our office.

![]()

Renewing and Revitalizing Icons of the 1960's

Reworking the fabric of renowned and beloved landmarks, however beset they may be with neglect and the passage of time, is a daunting yet deeply satisfying challenge. Evolving values and perceptions overlay the standing achievements of the influential and innovative designers of preceding decades- or centuries- leaving the contemporary designer with penetrating questions of what to change and what to restore. This is indeed no less of a dilemma when the subject is a modern or modernist icon. Principles are essential to the endeavor. In seeking a balance of respect and renewal, we look to function and use: ultimately the greatest respect we can show to an important monument or period example is to restore it to active life as an integral, vital part of its ever-changing world. Here we show two widely varied examples of this profoundly humbling task- both in California, and both from a recent past that is still very much alive.

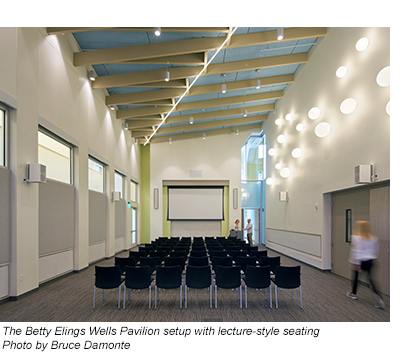

Sympathy for the Disrupter: Expanding the Legacy of Charles Moore’s Faculty Club

A few years ago, the University of California, Santa Barbara, tapped us to carry out the renovation, adaptive reuse, and expansion of its Faculty Club, the circa 1968 internationally revered icon of irreverence designed by Charles Moore, with William Turnbull of MLTW. Our selection may have been influenced by our personal connection to Charles and to the unconventional spirit in which he designed the building. Staying true to that spirit was at the core of all our decisions—which meant our solutions weren’t conventional either. To save the Faculty Club, we had to transform it.

The Restored UCSB Faculty Club

The Restored UCSB Faculty Club

Photo by Bruce Damonte

Born of a wide-ranging, exploratory design process, the original 10,000-square-foot facility immediately drew international attention for its sloping shed-roofed towers, dramatic high windows, daylight- flooded spaces, and pop-art interiors complete with strings of lights, and neon banners. On the campus, reactions to the design varied. Some faculty members found it glorious and beautiful, a modern contrast to the drab structures on campus. Others reacted negatively. Whatever else, it fulfilled the architect’s intention to stir the senses, and became an icon for the campus and, eventually, for architects everywhere.

The Faculty Club was indeed brilliantly designed, but its complicated, low-budget construction left it particularly vulnerable to the passage of time, and the needs of the campus expanded well beyond its capa

city. Our assignment was to fully renovate it and double it in size, adding guest rooms and increasing dining and meeting space. In doing so we sought to reconnect with Charles’ unique spirit and some of MLTW’s methodology as well. We assembled a detailed digital model of the original structure, but we studied the design using a ¼-inch scale cardboard model, just as MLTW would have done. And while Charles’ décor of estate-sale treasures added character, our approach focused more on the architecture itself and in some ways was as experimental as his original design: celebrate the original opus but radically change the way the building functioned for contemporary use.

city. Our assignment was to fully renovate it and double it in size, adding guest rooms and increasing dining and meeting space. In doing so we sought to reconnect with Charles’ unique spirit and some of MLTW’s methodology as well. We assembled a detailed digital model of the original structure, but we studied the design using a ¼-inch scale cardboard model, just as MLTW would have done. And while Charles’ décor of estate-sale treasures added character, our approach focused more on the architecture itself and in some ways was as experimental as his original design: celebrate the original opus but radically change the way the building functioned for contemporary use.

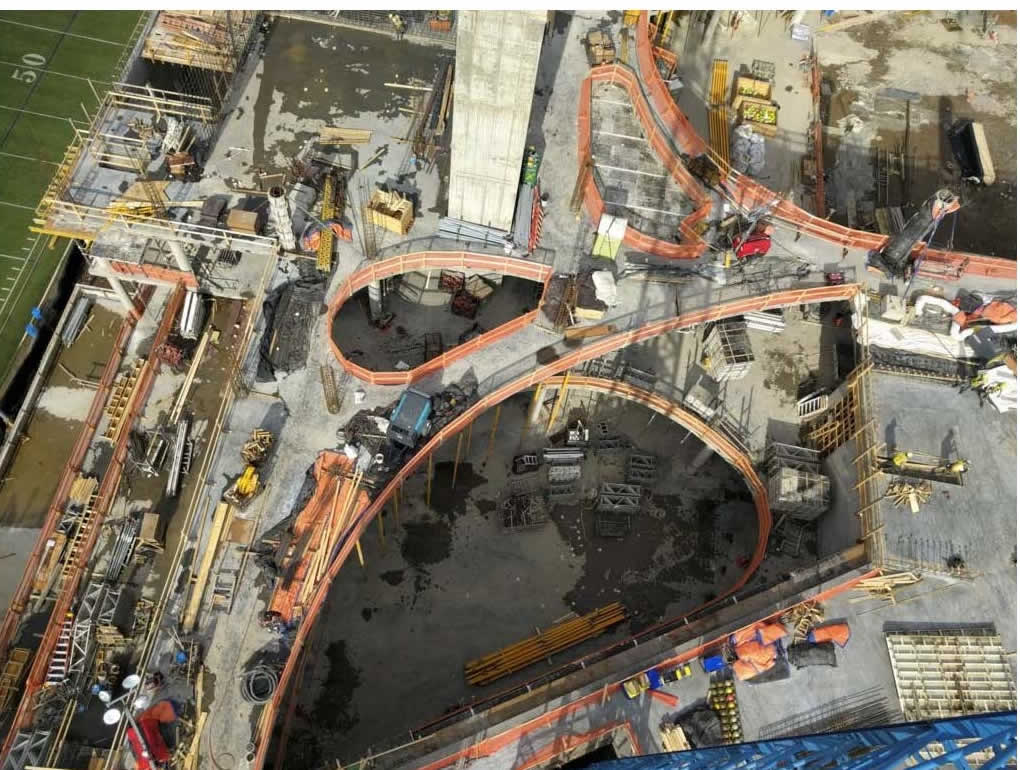

The main part of our brief was to add 30 guest rooms, with a new three-story wing of guest rooms on the west side, which meant removing the patio, pool, and changing rooms. That was a big change, but the swimming pool was the aspect of the original design that was the least relevant to the university’s current needs. To attach the guest-room wing, we took out a small two-room tower and replaced it with a connecting stair tower. An open-air rotunda was removed and then rebuilt as enclosed space with a skylight.

On the north side, we put in a new stairway, which breaks up what had been a large blank wall and provides a gracious entry into the dining room from the guest rooms. In doing so, we replaced the original dining room stair with a stair that allowed for more flexible layouts—one of two significant revisions to the iconic image of the building. The second revision was to enclose the open courtyard, which had become a damp and moldy interval at the heart of the complex. Two stories high, contemporary in style but retaining the spirit of the original building, it’s now a place that can comfortably host wedding receptions, lectures, performances, meetings, and other gatherings and events.

Our work on the main dining room mostly involved restoration. But even here we felt transformation was called for, so we added color into the layered set of walls that frame the space, hidden from view as you look out from the center. The sun coming in through high windows lights up these color spaces, creating a glow that heightens the perception of the layered poche of structure surrounding the dining room.

As a firm, we’ve always tried to embody the sense of immediacy and spontaneity in Charles’ work, even as we strive for a long and useful life for each project. For the Faculty Club, we wanted a conversation with Charles’s original thoughts about the building, responding rather than mimicking. Our goal was to breathe new life into the Faculty Club in a way that speaks to Charles Moore’s one-of-a-kind sensibility. We hope he would be pleased.

A point of cultural inflection: transformations of the 1960’s at UC Berkeley

MLK is Expanded and Opened to the Plaza

MLK is Expanded and Opened to the Plaza

Photo by Bruce Damonte

Both the UC Santa Barbara Faculty Club and the UC Berkeley Lower Sproul Student Center were designed and built during the 1960’s. This was a time of cultural revolution. Charles Moore breezed into New Haven to become Dean of the Yale School of Architecture in 1965, fresh from the rumblings of Berkeley. He championed a democratic, irreverent and affordable architecture, giving voice to the transformations that were roiling the culture at large.

The Lower Sproul Student Center was conceived between 1948 and 1955, designed in 1957, and built between 1958 and 1968. The 1957 competition winning design led by Vernon DeMars of Hardison and Demars was designed as a multi-building “town center” organized around a plaza designed by Lawrence Halprin. Each of the four major buildings had a unique structural and formal expression. They were united by the predominant expression of concrete construction, representative of the “new brutalism”, complimented by a range of decorative elements redolent of bay area traditions.

The ensemble was both hailed as a bold expression of modern architecture and criticized as harsh and quirky. The Center was immediately successful at providing a focus of student life and in recognizing the synergies between dining, study, performance and student organizations.

From its inception, the Student Center has been a place of expression and dialogue- in 1964 the Free Speech Movement led by Mario Salvi became an epicenter of student activism. Ironically, at this point of cultural inflection, the DeMars scheme exemplified the bold heroic architecture of his time, but the cultural winds of a populist movement were already blowing.

Over the years, the concrete bones of the four major buildings held up as a bold expression. The less successful aspects of of this strong expression included its harshness and lack of flexibility. Over time the plaza was not welcoming for gathering and the complex became increasingly dysfunctional.

Beginning as early as 1968 renovations were undertaken in response to functional and seismic needs. Through the years numerous schemes were proposed, culminating in a dramatic 600 million dollar plan that would have completely replaced MLK Student Union and Eshelman Hall, the home of student organizations.

The New Eshelman hall Creates Portals to the City

The New Eshelman hall Creates Portals to the City

Photo by Alan Karchmer

We were hired near the start of the 2008 recession. We began with a fresh look at all aspects of planning and programming. We recommended a new approach which included very selective interventions to create catalytic change at a much more affordable scale.

We sought to respect the tough but rigorous language of MLK, but also to activate it at pedestrian levels; to make the entire complex more permeable to the adjacent city neighborhood; to replace the seismically dangerous and physically inflexible Eshelman hall with a lower more porous and flexible building; and to redesign the landscape and plaza for accessibility and activation. Fortuitously, Eshelman Hall was DeMar’s least favorite building, about which he had expressed regrets.

Our approach led to the strategic leveraging of existing facilities. It allowed us to create a revitalized district rooted in sustainable practice and to optimize resources. The new district could now be achieved for $150 million or one quarter of earlier plans.

We developed the new vision, program and design through extensive participatory workshops with students, faculty, staff, community and civic leaders:

A Shared Vision for the Student Community Center emerged as a...

HOME for renewal, participation and performance

FORUM for dialogue diversity and civic engagement

LABORATORY for learning, living and demonstrating a sustainable future

GATEWAY for connecting the campus and community

The plan balances physical and program needs, celebrates the diversity of the community and creates a heart for student life and learning. Technology and building systems are designed for sustainability and long-term flexibility. Interior and exterior spaces are designed for 24/7 activity including: student services, student organizations, maker spaces, performance spaces, social and meeting spaces, meditation spaces, and retail. Food service includes an array of socially responsible and farm to table providers.

At the southern boundary along Bancroft Way, the new Eshelman Hall and the renovated MLK provide a Welcome center, Transit center, community serving retail and large portals to connect the campus to the City of Berkeley. At the northern edge of the site, our master plan provides visual and pedestrian connections to the historic Strawberry Creek and a restored riparian ecosystem.

The design process allowed for a broad consensus, building on the aspirations of the community, and creating a vibrant new heart of campus life. As a result, the 1957 winning design was respected, renewed and reinvigorated for a new generation.

MLK and New Eshelman Animate The Plaza with Active Uses

MLK and New Eshelman Animate The Plaza with Active Uses

Photo by Alan Karchmer

![]()